A Dazzling Transformation at The Museum of Flight

South African artist Ralph Ziman invites visitors to experience his most striking artwork: a decommissioned Soviet MiG-21, now cloaked in a million rainbow-coloured glass beads, lovingly arranged one bead at a time. The fighter jet, once a leaf of fire in military time, has been repurposed into a mosaic of reconciliation, taking its rightful place at The Museum of Flight. Hidden within its glossy lacquer lies 12 years of labour and longing. This piece is the climax of his international installation series, “Weapons of Mass Production.”

The exhibit, which opened June 21, 2025 and continues through January 26, 2026, is much larger than the jet alone. Marking the fusion of art and aeronautics, the museum has also installed technicolour Afrofuturistic flight suits, dramatic photographs, and hands-on displays. Visitors can explore the shadowy years of the Cold War, the repurposement of military airframes, and the much older heritage of beadwork through the lens of African artistry. For Ziman, “Mass Production” is the conclusion of his personal trilogy. The trilogy has carefully and defiantly transformed sumptuous beadwork into a new matter of personal, communal, and global healing.

The Vision Behind the Beads: An Artist’s Journey

Ralph Ziman’s “Weapons of Mass Production” series started long before the art materials hit the workbench—its spark came from life in apartheid South Africa. Growing up in the ’60s and ’70s in Johannesburg, military rifles weren’t just in the news, they were in the streets. Ralph Ziman figures he had a barrel pressed into his ribs about 15 or 20 times by age 50. Each interrogation deepened a simple truth: guns breed fear, not safety. The shock of these moments birthed a quiet promise: if ever he could speak to the world through art, it would be to question why firepower is normalized.

After decades in the music and advertising industries—snapping million-selling album covers and coding hyper-stylized music videos for icons like Michael Jackson and Toni Braxton—Ziman stepped beyond the commercial studio’s glare. In 2013 he pitched his first petition to the past: the AK-47 Project. Beads, shards of reflection and memory, swallowed replicas of the world’s most infamous rifle.

Three years later, his fingertips translated trauma into the Casspir Project, turning an armored personnel carrier—an apartheid-era people intimidator—into a travelling canvas of peace and color. The trilogy reached for the sky with the MiG-21 Project, literally. Now a retired Cold War jet, the plane is Ralph Ziman’s most labor and logistics-heavy endeavor, a chance to unify land, sky, and memory under a beaded membrane of dialogue.

The Making of the Beaded MiG-21: Five Years, 35 Million Beads, and a Worldwide Team-Up

Turning a warplane into a colorful, glittering work of art took a breathtaking five years and at least a hundred dedicated craftswomen from the Ndebele communities of Mpumalanga, Johannesburg, and KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. Starting the journey, artist Ralph Ziman purchased a retired, non-operational MiG-21 from a Florida defense contractor. The tired jet was airlifted to his studio in Los Angeles, where it was carefully taken apart, and every inch was mapped for beaded decoration.

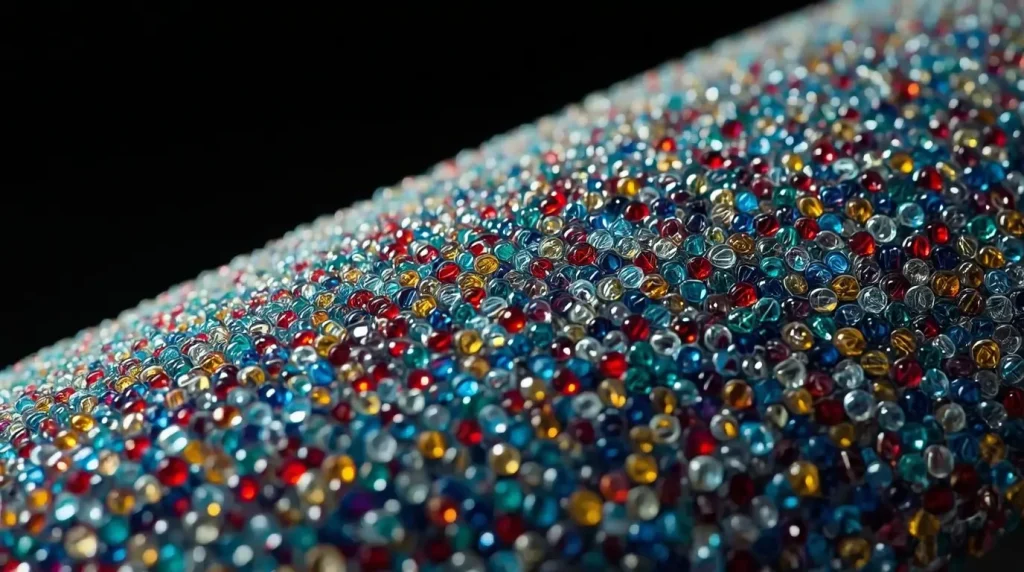

Each design was first sketched on a paper template taped onto the jet’s aluminum skin, then the prepared parts were sent to South Africa. There, the artisans beaded every section by hand, using techniques that have been cherished and shared across generations. The largest aluminum pieces spanned over 20 feet and weighed an impressive 30 to 40 pounds once the beads were in place. In the end, the masterpiece needed 35 million tiny glass beads, and every single one was threaded by hand—no machines, just skill and patience.

The beadwork we see here blends many African styles. Instead of belonging to one tribe or region, the geometric shapes and color combinations pull inspiration from craftspeople coast to coast. By using this pan-African vision, the artists honor a continent-wide heritage and spark a conversation about sharing, learning, and creating together. The beading is led by Thenjiwe Pretty Nkogatsi, founder of the Anointed Hands collective. Under her guidance, a group of women keeps Ndebele beadwork alive while also pushing its boundaries for a global audience.

Ralph Ziman views the artwork as a canvas for social change, not just decoration. The trilogy “Weapons of Mass Production” expands its gaze from the gallery to the street and directly confronts the worldwide arms business and the growing militarization of everyday policing. Ralph Ziman draws a stark line between history and today: a Casspir armored vehicle once feared in South African neighborhoods shows up in footage from the U.S., rolling by during a Black Lives Matter march. The streets of one continent turn canvas and mirror for another, proving how instruments of shaming and control can change uniforms but remain the same toolbox of power.

The project does more than just create art—it delivers real help. Through DTGruelle, the logistics company backing the effort, 25 kids linked to the artisans now enjoy scholarship support. Once it sells, the MiG-21’s profit will fund art therapy programs for kids in Ukraine. In this way, a Cold War fighter connects to the very children hurt by today’s Ukraine conflict, turning a weapon into a source of healing 16.

Ralph Ziman offers a clear take: “I love the idea that what was once a Soviet gift now helps patch up the civilian toll, the brutal civilian toll, from the war with Russia.”

An Exhibit that Reaches Outside the Classroom

Seattle’s Museum of Flight turns into the right stage for the MiG-21 project. The museum puts the beaded fighter, a canvas of history, inside the Pavilion while three halls display Ziman’s sketches, video mixes, and a collection of clothing that pop and impress 47. Together, the MiG-21 and all the pieces by Ralph Ziman and his crew invite visitors to see conflict history in a fresh way.

The Afrofuturistic flight suits mirror the aircraft’s beadwork and fuse influences from military fashion, African tribal cloth, and imagined space gear. This look sketches a parallel world where a jet as bright as a bead necklace gets serviced by a crew dressed in gear bright enough to rival it. In the same breath, the suits carry the heavy pulse of Afrofuturism—an art movement that began as a shout for social justice and fairness—painting the project with a richer shade of meaning.

Museum CEO Matt Hayes points out that the display reaches farther than just metal and engines: “If we were only listing specs, we’d be talking about the MiG’s altitude and the number of cannons it carried. That’s not the conversation we care about. Luckily, artists like Ralph Ziman and the crew of creators with him uncover humanizing tales in ways that land hard—really, really hard—yet beautifully.”

The Enduring Legacy of Ralph Ziman’s Beadwork

Ralph Ziman’s art moves far beyond reconceiving guns; it reimagines African beadwork itself. By magnifying this centuries-old craft to the realm of fine art, the artist rescues it from the “tourist craft” category. “I’ve always loved beadwork,” he says. “I grew up with it—my Ndebele nanny always brought us colourful bead objects. Despite the skill involved, it was dismissed. I wanted to lift it into the conversation of fine art.”

Ralph Ziman’s latest effort demonstrates that collaborative creativity survives crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic grounded flights and closed borders, yet the team stayed invested. “The ladies in the workshop could not get visas to the U.S.,” he explains, “but they flipped to virtual. They streamed videos, sent instructions through texts and WhatsApp. In the end the project not only finished, the final piece saw the beads shine brighter.”

Conclusion: A Symbol for Our Times

While conflicts flare across the globe, Ralph Ziman’s beaded MiG-21 proves that art can flip stories of violence into invitations for peace, memory, and cultural exchange. Ralph Ziman reminds us, “The project may even matter more now than when we first began.”

Visitors stepping into The Museum of Flight encounter more than a one-of-a-kind artwork; they meet a chance to ponder how yesterday’s symbols can be re-drawn for a brighter tomorrow. Once a badge of superpower rivalry, the jet now soars as a shining symbol of shared creativity and international resilience.

The MiG-21 Project will remain on view at The Museum of Flight in Seattle until January 26, 2026. More information can be found on the museum’s website. To explore the broader Weapons of Mass Production trilogy and the artist, visit ralphziman.com.

Source: https://edition.cnn.com/world/africa/ralph-ziman-mig-21-weapons-of-mass-production-spc

For more incredible stories of everyday news, return to our homepage.